A Coffee Withdrawal Diagnosis

Quitting Caffeine Is Now Listed as a Mental-Health Disorder; The Best Ways to Break the Habit

Caffeine is now worthy of two official

diagnoses in the mental health diagnostic manual. Sumathi Reddy looks at

what techniques work to reduce coffee addiction, and why some people

have a harder time quitting than others. Photo: Getty Images.

Kim Leadley didn't think much of her one- or two-a-day Starbucks Grande coffee fix.

But when she tried to go cold turkey to stop the habit, she found

herself getting headaches—excruciating headaches, the

I-can't-work-think-or-function kind of headaches, she says. Within days,

she "fell off the wagon" and resumed the coffee habit.

"The headaches did make me think there was something to be said for

caffeine addiction" and withdrawal, said the 41-year-old Cumberland,

Maine, resident. She started tapering off her caffeine consumption by

mixing decaffeinated and regular coffee. About six months later, she

finally kicked the habit for good after getting pregnant in December.

Caffeine, that most-benign seeming drug of choice that keeps so many

of us fueled through the day, is now the basis of two official diagnoses

in the mental-health bible released in May, with a third brewing for

consideration. The latest version of the American Psychiatric

Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

commonly referred to as DSM-5, includes both caffeine intoxication and

withdrawal. These conditions are considered mental disorders when they

impair a person's ability to function in daily life.

Caffeine intoxication was included as a

diagnosis in the previous version of the manual, known as DSM-IV. But

caffeine withdrawal was upgraded in the current manual to a diagnosis

from a "research diagnosis" previously, meaning it required further

study for inclusion. Also, caffeine use disorder—when a person suffers

troubling side effects and isn't able to quit—was added to the current

manual as a research diagnosis.

The designations didn't come without controversy.

"Caffeine intoxication and withdrawal both occur fairly frequently

but only rarely cause enough clinically significant impairment to be

considered a mental disorder," said Allen Frances, who chaired the task

force that developed the previous version of the DSM and has been a

vocal critic of the latest version. "We shouldn't medicalize every

aspect of life and turn everyone into a patient," he added.

Alan Budney, a member of the DSM-5 Substance-Related Disorders Work

Group, said the research in support of caffeine withdrawal as a

diagnosis is substantial. It is a "clinically meaningful" diagnosis that

could be useful to psychiatrists and other health-care workers seeing

someone experiencing such symptoms, said Dr. Budney, a psychiatry

professor at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College.

"The symptoms [of caffeine withdrawal] overlap with a lot of other

disorders and medical problems," said Laura Juliano, a psychology

professor at American University who advised the DSM-5 work group.

"We've heard many times people went to the doctor for chronic headaches

or because they thought that they had the flu and it turns out it was

caffeine withdrawal and they didn't even know it."

Although caffeine is addictive, many studies have found the drug is

associated with some health benefits. Still, some experts say certain

individuals should avoid caffeinated products, such as those with

anxiety, high blood pressure, insomnia and diabetes. People who

experience adverse effects from caffeine, such as the jitters typically

associated with caffeine intoxication, may want to consider at least

scaling back their consumption.

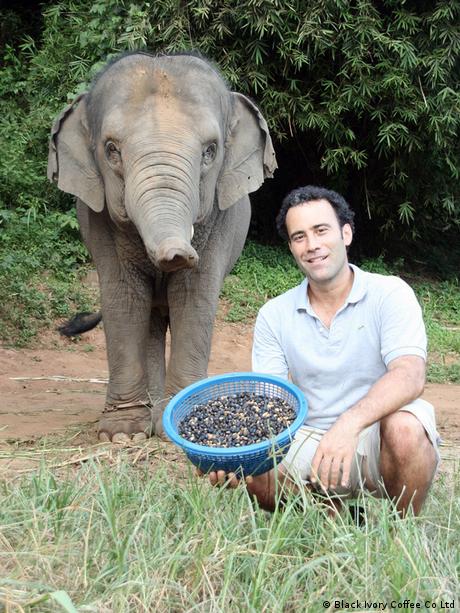

When Kim Leadley of Maine quit coffee cold turkey, the headaches were debilitating.

To be diagnosed with caffeine

withdrawal, a patient must experience at least three of five symptoms

within 24 hours of stopping or reducing caffeine intake: headache,

fatigue or drowsiness, depressed mood or irritability, difficulty

concentrating, and flulike symptoms such as nausea or muscle pain.

OK, who hasn't experienced some of these when they skip that morning cup of Joe?

Here's the caveat though. The symptoms, Dr. Budney stressed, must

cause "clinically significant distress or impairment" that affects your

functioning at work, home or in a social setting.

Caffeine intoxication is defined as having five of a dozen symptoms.

Among these are restlessness, flushed face, nervousness, insomnia,

muscle twitching, irregular heartbeat and rambling flow of thought and

speech. Again, these symptoms must make it extremely hard to function at

work or home. Intoxication can occur at levels in excess of 250

milligrams of caffeine, according to the DSM. But experts say most cases

of intoxication result from much higher doses.

Genetic differences in a liver enzyme affect how quickly people

metabolize caffeine, said Ahmed El-Sohemy, an associate professor in the

Department of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Toronto.

Ridding the body of half the caffeine consumed can take as many as eight

hours for some people, while others may require as few as two. Smoking

speeds up caffeine metabolism, making it about twice as fast, whereas

pregnancy or oral contraceptives slow it down, Dr. El-Sohemy said.

"Some people cannot drink any coffee, half-a-cup of coffee or a Coke

will keep them up at a night," said Jim Lane, a professor of behavioral

medicine at Duke University School of Medicine. However, "if a person

doesn't have any unpleasant symptoms, or any health problems that we

know are affected by caffeine use, then I would not try to suggest that

whatever they consume is too much," he said.

Caffeine-withdrawal symptoms usually kick in about 12 hours after

consumption, peaking at 24 hours, Dr. Lane said. For most people all

symptoms should disappear in about a week, he said. That may be

preferable to spending several weeks slowly cutting back, only to find

that the final step of quitting still leads to withdrawal, he said.

Roland Griffiths, a professor in the department of psychiatry and

neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, runs an

on-and-off-again clinic for caffeine treatment for patients with

conditions made worse by caffeine consumption. Treatment involves

counseling patients about the amounts of caffeine in various beverages

and food products. Patients graph their daily caffeine intake for a

week. "Then we get them to gradually reduce their caffeine intake over a

period of weeks," said Dr. Griffiths. That can be done by mixing

caffeinated and decaffeinated drinks and cutting caffeine by, say, 25% a

week.

Among regular caffeine drinkers who abstain from caffeine, headache

is reported about 50% of the time and functional impairment about 13%,

said Dr. Griffiths, who advised the DSM-5 work group. But even if people

don't have a headache they may have fatigue or an inability to

concentrate, he said. "That's why I think the prudent and the least

painful way to do it is fade caffeine use out over time."

For people who don't want to completely give up caffeine, but don't

want to be dependent on it, Dr. Juliano of American University

recommends drinking it at irregular intervals, and limiting it to as

close to 100 milligrams as possible.

Dr. Griffiths, of Johns Hopkins, said he has caffeine intermittently,

perhaps once a week, in relatively small doses. "If I'm sleep deprived,

it's a really effective drug. It's very useful if you're not dependent

on it because then it's more powerful and more effective and you don't

have any withdrawal," he said.

Write to Sumathi Reddy at

sumathi.reddy@wsj.com